Brentwood Local Plan 2016 - 2033 (Pre-Submission, Regulation 19)

5. Resilient Built Environment

(1) 5.1 It is increasingly recognised that the design and layout of our built environment can impact our well-being and the opportunities to live a healthy lifestyle.

5.2 The role of planning policies and decisions in enabling and supporting healthy lifestyles is recognised in the NPPF (2018, paragraph 91).

5.3 The NPPF (2018, section 14) emphasises the need to take a proactive approach to mitigating and adapting to climate change. Our built environment is often put under strain during extreme weather conditions. The policies in this section seek to avoid increased vulnerability to extreme weather conditions, to ensure infrastructure is built to be resilient under conditions of a changing climate, and to ensure development is planned in ways that reduce carbon emissions, providing a positive strategy for resource efficiency. The Council seeks to improve our built environment so that it can support the future resilience of communities and infrastructure, as well as create strong, vibrant and healthy communities.

5.4 Infrastructure plays a critical role in enabling communities and businesses to survive and flourish in the face of climate and other threats. The concept of resilience in a planning context can be understood as the ability to reduce exposure to, prepare for, cope with, recover better from, adapt and transform as needed, to the direct and indirect consequences of climate change, where these consequences can be both short-term shocks and longer-term stresses[1].

5.5 Resilience-building strategies can be considered to be 'reactive' or 'proactive'[2]. A reactive approach focuses on mitigating consequences, maintaining stability and the status quo, whereas a proactive approach focuses on change and adaptation and looks more towards addressing long term stresses. Both approaches are incorporated in this Plan.

5.6 A holistic approach to sustainable development that reduces the environmental impact of development whilst healthy planning should be embedded within all development proposals from the outset.

5.7 The policies in this section aim to increase the efficiency and resilience of our infrastructure, making our borough smarter and better prepared for climate impacts and other threats.

Future Proofing

(6) Policy BE01: Future Proofing

- In planning and design for resilience, all applications

must take into account the following principles of future

proofing:

- well-being, safety and security for residents and/or users;

- adaptable and flexible spatial planning and design;

- life cycle duration of infrastructure and buildings, including appropriate maintenance plan for the life of the development;

- potential hazards including fire, pest, flood, and climate change long term stresses in determining design, locations and installations of protection facilities, systems and buildings for the life of the development;

- existing and potential source of pollution, such noise and air, and according mitigation measures;

- increased quality of materials and installation;

- multi-functional green and blue infrastructure in line with the principles of Sustainable Drainage (SuDs) and natural flood management as part of the wider green and blue infrastructure network to deliver multiple benefits;

- provision of class leading digital connectivity infrastructure and other future essential technology; and

- delivery phasing that takes into account demand and supply if and where appropriate.

- Time horizons for proposed future-proof interventions can vary depending on the size, location and purpose of development but long-term time horizons based on objective and realistic assessment should be made clear in the proposal.

5.8 The term 'future-proofing' refers to the process of anticipating the future and developing methods of minimising the effects of shocks and stresses of future events. The concept is a critical component of resilience building strategy.

5.9 This policy requires applicants to consider:

- reactive measures to minimise the potential of and prepare for short-term shocks (such as pests, diseases, fire, flood, heatwave, etc.); and

- proactive strategies to adapt to long-term changes caused by climate change and technology development, through sustainable design, energy conservation, adaptable and flexible engineering, and other effective means.

5.10 Time horizons for future-proof interventions often depend on several variables but having a long-term vision and strategies, at least for the life of the development, can help plan ahead and defer the obsolescence and consequent need for demolition and replacement of structures, avoiding cost and service disruption.

5.11 Today, our social interactions, ways of doing business, travelling and other activities are supported and governed by digital connectivity. Not only is digital infrastructure an essential of today's economy but it is also critical in events of disturbance and is increasingly used to assist people with a range of health conditions. Space for digital infrastructure should be designed and installed as an integral part of development to minimise cost and disruption involved in the installing and retrofitting in line with Policy BE10 Connecting New Development to Digital Infrastructure.

5.12 Economic and business cycles, retail trends, among other market events, inevitably account for degree of uncertainty in the delivery and phasing of development, especially larger sites. This in turn, has consequent impacts on the built environment and the local housing market. Therefore, applicants should consider their impacts on delivery as far as it is appropriate and realistic to do so, and have appropriate measures and plans in place.

(1) Responding to Climate Change

(1) 5.13 Climate change and its consequences including flooding, heatwave and drought are significant environmental challenges and mitigating them is key to sustainability. Globally, the average concentration of CO2 now exceeds 400 parts per million, the highest in recorded history[3]. Sixteen of the seventeen warmest years on record have occurred since 2001[4]. The Environment Agency predicts an average sea level rise around the UK of at least a metre by 2115 from a 1990 baseline[5].

5.14 The Climate Change Act (2008) legislates for an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions against 1990 levels by 2050. This requires everyone to be engaged, from national and local government to businesses, households and communities.

5.15 Building the resilience of wildlife, habitats and ecosystems to climate change, to put our natural environment in the strongest position to meet the challenges and changes ahead is one of the objectives of the National Adaptation Programme 2018[6]based on key recommendations from the Climate Change Risk Assessment 2017[7]. This is addressed further by a number of policies, such as Policy BE18 Green and Blue Infrastructure, Policy NE01 Protecting and Enhancing the Natural Environment, NE02 Recreational Disturbance Avoidance and Mitigation Strategy (RAMS), Policy NE03 Trees, Woodlands, Hedgerows, NE05 Air Quality, and NE06 Flood Risk.

(2) 5.16 The policies in this chapter require decision takers and developers to give an appropriate consideration to addressing the climate change, including:

- climate change mitigation measures which focus on

reducing the impacts of human activities on the climate

system, by means such as:

- designing new communities and buildings to be energy and resource efficient;

- incorporating renewable technologies;

- reducing existing and potential source of pollution;

- reducing transport related carbon emissions through the promotion of sustainable modes of transport; and

- climate change adaptation measures which focus on

ensuring that new developments and the wider community are

adaptable and resilient to the changing climate, by means

such as:

- buildings, infrastructure and construction techniques that are designed to adapt to a changing climate and to avoid contributing to its impacts, including urban heat island effect;

- safe and secure environment which is resilient against the impacts of climate change long term stresses and extreme weather events;

- enhancing biodiversity and ecological resilience where possible;

- efficient resource management measures that take into

account issues such as,

- allocation and density of development;

- resource consumption (including water, energy, construction materials) during construction and operation as well as the environmental, social and economic impacts of the construction process itself and how buildings are designed and used.

Sustainable Construction and Resource Efficiency

5.17 Consideration of sustainable design and construction issues should take place at the earliest possible stage in the development process. This will provide the greatest opportunities for a well designed and constructed development and at the same time enable costs to be minimised. Therefore, developers should consider sustainable construction issues in pre-application discussions with the Local Planning Authority. Proposals should be captured within a Sustainability Statement, which can form part of the Design and Access Statement.

(10) POLICY BE02: Sustainable Construction And Resource Efficiency

The Council will require all development proposals, including the conversion or re-use of existing buildings, to:

- maximise the principles of energy conservation and efficiency in the design, massing, siting, orientation, layout, as well as construction methods and use of materials;

- submit details of measures that increase resilience to the threat of climate change, including but not limited to summertime overheating;

- demonstrates how the water conservation measures were incorporated in the proposals;

- incorporate suitable Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDs);

- incorporate the reduction in the use of mineral resources, including an increase in the re-use of aggregate; and

- include commercial and domestic scale renewable energy and decentralised energy as part of new development.

5.18 Sustainable design and construction are concerned with the implementation of sustainable development in individual sites and buildings. It takes account of the resources used in construction, and of the environmental, social and economic impacts of the construction process itself and how buildings are designed and used. Major development should also refer to Policy SP05 Construction Management.

5.19 The choice of sustainability measures and how they are implemented may vary substantially from development to development. However, the general principles of sustainable design and construction should be applied to all scales and types of development. More guidance on areas to be covered in the Sustainability Statement is set out in Figure 5.1.

|

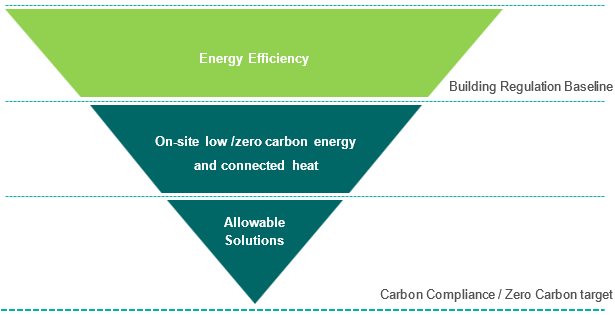

Adaptation to climate change Adaptation measures can be implemented at a variety of scales, from individual buildings up to community and conurbation scale. Measures that will have benefits beyond site boundaries, and that will have a cumulative impact in areas where development is to be phased, should also be pursued. Applicants should refer to best practice guidance. Carbon reduction Proposals should demonstrate how the carbon reduction target will be met within the energy hierarchy, as illustrated in Figure 5.2, in particular how the proposals:

Proposals for major development should contain a calculation of the energy demand and carbon dioxide emissions covered by Building Regulations and, separately, the energy demand and carbon dioxide emissions from any other part of the development, including plant or equipment, that are not covered by the Building Regulations (i.e. the unregulated emissions), at each stage of the energy hierarchy. Proposals should also explain how the site has been future-proofed to achieve zero-carbon on-site emissions by 2050. Water management Development must optimise the opportunities for efficient water use, reuse and recycling, including integrated water management and water conservation. Site waste management Developments should be designed in a way that reduces the amount of construction waste and maximises the reuse and recycling of materials at all stages of a development's lifecycle. All new development should be designed to make it easier for future occupants to maximise levels of recycling and reduce waste being sent to landfill. In order to do so, storage capacity for waste, both internal and external, should be an integral element of the design of new developments. The Council will be supportive of innovative approaches to waste management. Use of materials All new developments should be designed to maximise resource efficiency and identify, source, and use environmentally and socially responsible materials. There are four principal considerations that should influence the sourcing of materials:

Other As well as the consideration of the above issues, the sustainability statement in support of the application should also address how the proposals meet all other policies relating to sustainability throughout the plan, including:

|

Figure 5.1: Areas to be covered in the sustainability statement and recommended approach

Renewable Energy and Low Carbon Development

5.20 The NPPF (2018) requires the planning system to support the transition to a low carbon future in a changing climate, encourage the use of renewable and low carbon energy and associated infrastructure in line with the Climate Change Act 2008.

5.21 The Brentwood Renewable Energy Study (2014)[8] states that around half of all energy used in the borough is from road transport, with a third from domestic use and about a fifth from the commercial and industrial sector.

5.22 Statistical information from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS)[9], indicates that Brentwood Borough has relatively high levels of domestic gas and electricity consumption. Over the period 2010 - 2015, Brentwood had the highest level of domestic customer mean gas consumption in the County and was also significantly higher than the England and East of England averages for the same period. Electricity usage for Brentwood ranks about 4th in the County and also significantly higher than the England and East of England averages for the period 2010-2015. One of the reasons for the higher domestic energy use in Brentwood maybe that homes in the borough are 13% larger than homes in England on average.

5.23 Transport emission in the borough is also higher than the national average due to increased car ownership and access to vehicles. Over the period of the Plan, energy use and carbon emissions may increase by 10% following a 'business as usual' trajectory.

(4) POLICY BE03: Carbon Reduction, Renewable Energy And Water Efficiency

- Proposals for renewable, low carbon or decentralised energy schemes will be supported provided they can demonstrate that they will not result in adverse impacts, including cumulative and visual impacts which cannot be satisfactorily addressed.

- Development should meet the following minimum standards

of sustainable construction and carbon reduction:

- New Residential Development:

|

Year |

Minimum sustainable construction standards |

On-site carbon reduction |

Water efficiency |

|

Up to 2020 |

In line with Part L Building Regulations |

At least a 10% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions above the requirements of Part L Building Regulations |

110 litres per person per day limit Major development is expected to provide more substantial water management measures, such as rain/grey water harvesting. |

|

2020 onwards |

In line with Part L Building Regulations |

In line with national nearly-zero carbon policy. If national nearly- zero carbon policy is unavailable, the previous target applies. However, the minimum improvement over the Building Regulations baseline may be increased to reflect the reduction in costs of more efficient construction methods. |

110 litres per person per day limit Major development is expected to provide more substantial water management measures, such as rain/grey water harvesting. |

- New Non-residential Development

|

Year |

Minimum BREEAM Rating* |

On-site carbon reduction |

Water efficiency |

|

Up to 2020 |

BREEAM 'Very Good' rating to be achieved in the following categories:

|

At least a 10% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions above the requirements of Part L Building Regulations |

BREEAM 'Very Good' rating to be achieved in category Wat 01 Major development is expected to provide more substantial water management measures, such as grey water harvesting. |

|

2020 onwards |

BREEAM 'Excellent' rating to be achieved in the following categories:

|

In line with national nearly-zero carbon policy If national nearly-zero carbon policy is unavailable, the 2016 - 2020 target applies. However, the minimum improvement over the Building Regulations baseline may be increased to reflect the reduction in costs of more efficient construction methods. |

BREEAM 'Excellent' rating to be achieved in category Wat 01 Major development is expected to provide more substantial water management measures, such as grey water harvesting. |

*: The version of BREEAM that a building must be assessed under should be the latest BREEAM scheme and not be based on scheme versions that have been registered under at the pre-planning stages of a project. Other construction standards, such as LEEDs or Passivhaus, will be supported provided that they are broadly at least in line with the standards set out above.

- Application of major development, where feasible, will be required to provide a minimum of 10% of the predicted energy needs of the development from renewable energy;

- Application of major development, including

redevelopment of existing floor space, should be

accompanied by a Sustainability Statement (see Figure 5.1

Areas to be covered in the Sustainability Statement) as

part of the Design and Access Statement submitted with

their planning application, outlining their approach to the

following issues:

- adaptation to climate change;

- carbon reduction;

- water management;

- site waste management;

- use of materials;

- Where these standards are not met, applicants must demonstrate compelling reasons and provide evidence, as to why achieving the sustainability standards outlined above for residential and non-residential developments would not be technically feasible or economically viable;

- Where on-site provision of renewable technologies is

not appropriate, or where it is clearly demonstrated that

the above target cannot be fully achieved on-site, any

shortfall should be provided via:

- 'allowable solutions contributions' via Section 106 or CIL. These funds will then be used for energy efficiency and energy generation initiatives or other measure(s) required to offset the environmental impact of the development;

- off-site provision, provided that an alternative proposal is identified, and delivery is certain.

Carbon reduction target: challenging policy environment and long-term direction

5.24 The UK Carbon Plan (HM Government, 2011) states that if we are to achieve the 2050 carbon target, by 2050 the emissions footprint of our buildings will need to be almost zero. The UK's Committee on Climate Change in 2015 reinstates that 'meeting the 2050 target will require that emissions from energy use - power, heat and transport - are almost eliminated'[10].

5.25 The UK Government scrapped the zero-carbon homes policy in summer 2015. Consequently, the UK's 2012 National Plan to meet the Directive will need a revision in light of the removal of the zero-carbon homes. Short-term policy on climate change since then suffers from uncertainty.

5.26 However, the Climate Change Act 2008 commits the UK Government by law to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80% of 1990 levels by 2050. In addition, as long as the UK is a member of the EU, it still has to comply with the EU's Energy Performance of Buildings Directive[11], which requires that by 2020 the demand from all new buildings in Member States is 'nearly zero-energy'. The Paris Agreement also has implications on the UK carbon reduction target[12].

5.27 Therefore, the long-term trajectory retains: 'we will move away from the use of fossil fuels for heating and hot water and towards low carbon alternatives such as heat pumps or heating networks. By 2050, emissions from heating and powering our buildings will be virtually zero.'[13]

5.28 In light of the challenging policy environment for energy planning and long-term direction, the Council takes a positive approach in supporting the transition towards a low carbon future and addressing the climate change. This is in line with the NPPF (2018, paragraph 148), which requires local planning authorities to 'contribute to radical reductions in greenhouse gas emissions'.

5.29 The government originally set targets to ensure all new homes are zero carbon by 2016 and all new non-residential buildings are zero carbon by 2019. Improvements in resource efficiency to meet this target was made through Building Regulations which set standards for design and construction that applies to most new buildings, regardless of type. In 2016, Part L of the Building Regulations introduced a change to the energy efficiency standard, raising it to the equivalent of Code for Sustainable Homes Level 4.

5.30 The Planning and Energy Act 2008 allows local authorities to set local targets for carbon emissions above Building Regulations. The Deregulation Act 2015 (S43) which removes this right has not been enacted, meaning authorities can continue to set policy above Building Regulations.

5.31 The achievement of national targets for the reduction of carbon emissions will require action across all sectors of energy use. High standard of construction in new development is important if the United Kingdom is to meet its legally binding carbon reduction targets.

5.32 To contribute to these targets, this policy requires an on-site reduction of at least 10 per cent beyond the baseline of part L of the current Building Regulations. The minimum improvement over the Target Emission Rate (TER) will be increased in 2020 and over a period of time in line with the national zero-carbon policy and reflect the costs of more efficient construction methods.

5.33 Regulation 25B 'Nearly zero-energy requirements for new buildings' of the Building Regulations will not come into force until 2019 at the earliest[14] and statutory guidance on how to comply with Regulation 25B is not available at the time of this Local Plan being published. All developments are required to comply with this Regulation when it comes into force. If the national zero carbon policy is still unavailable after 2020, the 2016 - 2020 target applies; however, the minimum improvement over the Building Regulations baseline will be reviewed.

5.34 According to the Brentwood Renewable Energy Study (2014), an international analysis of certified buildings has shown that the additional cost of achieving BREEAM 'Very Good' is expected to be minor and so therefore should not be burdensome for developers. The version of BREEAM that a building must be assessed under should be the latest BREEAM scheme and not be based on scheme versions that have been registered under at the pre-planning stages of a project.

5.35 There are many approaches that can be taken to meeting the construction standards required by this policy. The Council will be supportive of innovative approaches to meeting and exceeding the standards set out in the policy. Where other construction standards are proposed for new developments, for example Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) or construction methods such as Passivhaus Standard, these will be supported, provided that it can be demonstrated that they are broadly in line with the standards set out above, particularly in relation to carbon reduction and water efficiency.

5.36 The Council expects all new development to apply the energy hierarchy, set out in Figure 5.2, by reducing the need for energy, supplying energy efficiently, and using low and zero carbon technologies.

5.37 As part of the government's policy for achieving zero carbon performance, the policy seeks to establish realistic limits for carbon compliance (on site carbon target for buildings) and allows for the full zero carbon standard to be achieved through the use of 'allowable solutions'. These are envisaged as mainly near site or off-site carbon saving projects which would compensate for carbon emissions reductions that are difficult to achieve on site. Local authorities can explore opportunities for using carbon offset funds and community energy funds as a way of delivering the concept of allowable solutions in their areas.

(1) Water Efficiency

5.38 Brentwood Water Cycle Study 2018[15] identifies the borough as lying within an area of Serious Water Stress. A semi-arid climate and succession of dry winters can lead to groundwater levels within Brentwood being susceptible to multi-season droughts. The quality of the borough's watercourses is generally poor, while sewerage infrastructure in the north of the borough is operating at full capacity. The study recommends requiring all new developments to submit a water sustainability assessment and developers to demonstrate that they will achieve the water consumption reduction to Level 3/4 of the Code for Sustainable Homes for all residential developments and for non-residential developments to achieve BREEAM 'Very Good' standard for water consumption targets. As the Code for Sustainable Homes has been withdrawn, water conservation measures will be required to ensure a 110 litres per person per day limit, at the level formerly considered at Level 3-4 in line with the Water Cycle Study 2018.

5.39 Major developments are encouraged to incorporate more substantial water management measures, such as grey water harvesting. This is supported by the Interim Sustainability Appraisal (2016, paragraph 21.1.4 and 2018, paragraph 10.8.3).

5.40 For details on flood risk measures refer to Policy NE06 Flood Risk.

5.41 Incorporating renewable energy generation and energy efficiency measures into new development will be essential in order to achieve carbon reduction targets. The government has set a target to deliver 15% of the UK's energy consumption from renewable sources by 2020 yet in 2016, only 8.9% of our energy was met by renewable generation[16].

5.42 All developments should maximise opportunities for on-site electricity and heat production as well as use innovative building materials and smart technologies to reduce carbon emissions, reduce energy costs to occupants and improve the borough's energy resilience.

(5) POLICY BE04: Establishing Low Carbon And Renewable Energy Infrastructure Network

- Stand-alone renewable energy infrastructure

Community-led initiatives for renewable and low carbon energy, including developments outside areas identified in this Local Plan or other strategic policies that are being taken forward through neighbourhood planning, will be encouraged, subject to the acceptability of their wider impacts, including on the Green Belt.

- Decentralised energy infrastructure

The Council will work with developers and energy providers to seek opportunities to expand Brentwood's decentralised energy infrastructure.

- Strategic development that could play a key role in establishing a decentralised energy network should engage at an early stage with the Council, stakeholders and relevant energy companies to establish the future energy requirements and infrastructure arising from large-scale development proposals and clusters of significant new development. Applicants of these sites will prepare energy masterplans which establish the most effective energy strategy and supply options.

- New development of over 500 dwelling units, or

brownfield and urban extensions at 500 units or more, or

where the clustering of neighbouring sites totals over 500

units, will be expected to incorporate decentralised energy

infrastructure in line with the following hierarchy:

- where there is an existing heat network, new development will be expected to connect to it;

- where there is no existing heat network, new development will be expected to deliver an onsite heat network, unless demonstrated that this would render the development unviable;

- where a developer is unable to deliver the heat network, they need to demonstrate that they have worked in detail with third parties (commercially or community) to fully assess the opportunity;

- where a heat network opportunity is not currently viable and no third party is interested in its delivery, the development should be designed to facilitate future connection to a heat network unless it can be demonstrated that a lower carbon alternative has been put in place.

- New development will be expected to demonstrate that

the heating and cooling system have been selected according

to the following heat hierarchy:

- connection to existing CHP/CCHP distribution network;

- site-wide renewable CHP/CCHP;

- site-wide gas-fired CHP/CCHP;

- site-wide renewable community heating/cooling;

- site-wide gas-fired community heating/cooling;

- individual building renewable heating.

- Building scale technologies

Innovative approaches to the installation and/or construction of community and individually owned energy generation facilities or low carbon homes which demonstrate sustainable use of resources and high energy efficiency levels will be supported.

- Development in the Green Belt will be considered in accordance with Policy NE10 New Development, Extension and Replacement of Buildings in the Green Belt.

5.43 According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA, 2018)[17], renewable energy will be cheaper than fossil fuels by 2020 thanks to improvements in technology. The recent Global Status Report by REN21 (2018)[18] also states that renewable energy currently makes up a fifth of the world's electrical power supply, and its capacity has doubled over the past ten years. Renewables are experiencing a virtuous cycle of technology improvement and cost reduction. How policies can support the ability to connect with supply grid, rather than viability, will be the main challenge in the transition towards the low carbon future.

5.44 It is acknowledged that standalone technologies such as large-scale wind turbines and photovoltaic (PV) arrays could be significant sources of energy. The resource assessment in the Brentwood Renewable Energy Study (2014) demonstrated that the borough's renewable energy target will not be possible without deploying large commercial scale renewable technologies. However, stand-alone renewable energy schemes would occur within and could impact on the Green Belt and would also be constrained by proximity to suitable connection to the national electricity grid. Therefore, whilst the Council would encourage opportunities for stand-alone renewable energy schemes within Brentwood, this will need careful consideration and be assessed on a case by case basis. Selection of the most appropriate locations would depend on balancing technical factors (such as proximity to substations) with minimising the impact of those developments through careful siting and mitigation measures. The Council would also support community-led initiatives for renewable and low carbon energy, including developments outside areas identified in local plans or other strategic policies that are being taken forward through neighbourhood planning, in line with the NPPF (2018, paragraph 152).

5.45 Decentralised energy broadly refers to energy that is generated off the main grid, including micro-renewables, heating and cooling. It can refer to energy from waste plants, combined heat and power, district heating and cooling, as well as geothermal, biomass or solar energy. Schemes can serve a single building or a whole community, even being built out across entire cities. Decentralised energy is a rapidly-deployable and efficient way to meet demand, whilst improving energy security and sustainability at the same time. Other benefits of decentralised energy include:

- increased conversion efficiency (capture and use of heat generated, reduced transmission losses)

- increased use of renewable, carbon-neutral and low-carbon sources of fuel

- more flexibility for generation to match local demand patterns for electricity and heat

- greater energy security for businesses that control their own generation

- greater awareness of energy issues through community-based energy systems, driving a change in social attitudes and more efficient use of our energy resources

5.46 District heating and cooling systems (DH) are an important enabling technology for the use of renewables and need to be a central component of the decentralised system. DH can combine different sources of heat and can play a positive role in the integration of variable renewable energy. In 'the Future of Heating'[19] the government highlighted the role for heat networks for delivering low carbon heat. District heating can be retrofitted for existing heat customers or installed in developments as part of a site wide low or zero carbon energy solution.

5.47 The East of England resource assessment and the Brentwood Renewable Energy Study 2014 suggest that there are unlikely to be major anchor and high heat density areas in the borough suitable for retrofit-only DH networks. New development will therefore play an important role in heat network development in the borough. Strategic allocations could offer great opportunities to expand the borough's decentralised energy infrastructure and were identified in the Brentwood IDP, these include:

- Sites in the South Brentwood Growth Corridor masterplan area including Brentwood Enterprise Park and Dunton Hills Garden Village;

- Warley extension masterplan area;

- Officer's Meadows masterplan area.

5.48 According to the Brentwood Renewable Energy Study (2014), DH is a viable low and zero carbon energy solution for new development; the viability of DH and CHP schemes are improved with increased scale, density and mix of uses. Smaller sites close to large exiting loads, on the other hand, provide opportunities for collaboration which provides cost effective, energy efficient, low carbon heat and electricity.

5.49 The financial opportunity from DH schemes exists as there are economies of scale where the costs of providing a central heat source that also generates power, together with the associated distribution infrastructure, outweighs alternative means of complying with Part L. Where development occurs piecemeal, it is likely that individual developers for each site would choose traditional means of meeting Part L Building Regulations, which may result in a loss of opportunity.

5.50 Energy masterplanning at the large scale offers a unique opportunity to consider and plan for a robust infrastructure that will support the aspirations of a sustainable community – not only in terms of demand reduction, energy efficiency and renewable energy supply, but also in relation to water and waste management, transport and biodiversity. All these issues must be considered from the earliest stage and will have a major influence on the energy masterplan concept. Particular attention should be given to opportunities for utilizing existing decentralised and renewable or low-carbon energy supply systems and to fostering the development of new opportunities to supply proposed and existing development. Such opportunities could include co-locating potential heat customers and heat suppliers. Using the masterplanning process to map out zero-carbon and renewable energy opportunities in the area will help in identifying the potential for renewables at all scales, including community-scale schemes (TCPA, 2016, Practical Guides for Creating Successful New Communities, Guide 4: Planning for Energy and Climate Change).

5.51 An Energy Masterplan should identify:

- major heat loads (including anchor heat loads, with particular reference to sites such as schools, hospitals and social housing);

- heat loads from existing buildings that can be connected to future phases of a heat network major heat supply plant;

- opportunities to utilise energy from waste;

- secondary heat sources;

- opportunities for low temperature heat networks;

- land for energy centres and/or energy storage;

- heating and cooling network routes;

- opportunities for futureproofing utility infrastructure networks to minimise the impact from road works;

- infrastructure and land requirements for electricity and gas supplies;

- implementation options for delivering feasible projects, considering issues of procurement, funding and risk.

Building scale technologies

5.52 Brentwood Borough has relatively high levels of domestic gas and electricity consumption, therefore building-scale technologies have potentials to meet the borough's domestic energy demands. Building scale technologies often comprise permitted development and can be included in new development or retro-fitted to existing units. Building scale technologies with the greatest potential include rooftop solar technologies and biomass boilers in the commercial and industrial sector.

POLICY BE05: Assessing Energy Infrastructure

Proposals for development involving the provision of individual and community scale energy facilities from renewable and/or low carbon sources, will be supported, subject to the acceptability of their wider impacts. As part of such proposals, the following should be demonstrated:

- the siting and scale of the proposed development is appropriate to its setting and position in the wider landscape;

- the proposed development does not create an unacceptable impact on the local amenities, the environment, the historic environment, the setting of a heritage asset, or a feature of natural or biodiversity importance. These considerations will include air quality, as well as noise issues associated with certain renewable and low carbon technologies;

- any impacts identified have been minimised as far as appropriate;

- where any localised adverse environmental effects remain, these are outweighed by the wider environmental, economic or social benefits of the scheme;

- renewable and low carbon energy development proposals located within the Green Belt will need to demonstrate very special circumstances, and ensure that adverse impacts are addressed satisfactorily (including cumulative landscape and visual impacts) in line with Policy NE09 Green Belt and NE10 New Development, Extension and Replacement of Buildings in the Green Belt.

5.53 While the Council wishes to promote renewable and low carbon energy generation, there is also a need to balance this aim against other objectives for Brentwood, such as minimising pollution, and conservation, preservation and enhancement of the natural and historic environment.

5.54 Other policies in the local plan relating to the safeguarding of the natural and historic environment and the conservation and protection of national or locally designated sites and buildings should be taken into account in applications for energy schemes.

5.55 Potential impacts may be acceptable if they are minor, or are outweighed by wider benefits, including the environmental benefits associated with increased production of energy from renewable and low carbon sources, which will contribute to reducing carbon and other emissions.

5.56 In determining planning applications for the development of renewable or low-carbon energy, and associated infrastructure in the Green Belt, careful consideration will be given to the impacts of such projects on the Green Belt. Developers will need to demonstrate very special circumstances that clearly outweigh any harm by reason of inappropriateness and any other harm if projects are to proceed.

POLICY BE06: Improving Energy Efficiency In Existing Dwellings

To support the transition to a low carbon future, and to tackle issues of rising energy costs, applications for extensions to existing dwellings and/or the conversion of ancillary residential floorspace to living accommodation should be accompanied by cost-effective improvements to the energy efficiency of the existing dwelling. The requirements of this policy will apply where the following measures have not already been implemented:

- cavity wall and/or loft insulation at least to the standards stipulated by Building Regulations;

- heating controls upgrade;

- E, F and G rated boilers replaced with an A-rated condensing boiler; and

- draught proofing around external doors, windows and un-used chimney.

5.57 In order for Brentwood to contribute to the national targets for carbon reduction, there is a need to reduce emissions from existing buildings as well as new ones. This policy seeks to utilise the opportunities that arise for making cost-effective energy efficiency improvements when works to extend existing homes are undertaken.

5.58 The aim of the policy is to help homeowners implement measures that will enhance the energy efficiency of their homes, helping to reduce fuel costs at a time of rising energy prices. Domestic emissions are sensitive to the weather; therefore, the installation of proper insulation, heating control, condensing boiler and draught proofing will help achieve efficient energy use whilst alleviate many causes of damp and mould.

5.59 If the property has an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), this could also be submitted as part of the planning application to demonstrate the need to comply with the policy.

5.60 Care will need to be taken in applying the policy to listed buildings and other heritage assets, to ensure that they are not damaged by inappropriate interventions. The implementation of the policy will be case by case, with officers recommending measures that would be suitable for that particular property, bearing in mind its age, type of construction and historic significance. There may be cases where improvements cannot be made to an existing dwelling without causing harm to the significance of the heritage asset, and in such circumstances the requirements of this policy will not be implemented.

5.61 The Energy Saving Trust's website[20] offers useful guides on energy efficiency improvements in the home, as well as the cost of these measures and how much they save home owners' energy bills.

POLICY BE07: Managing Heat Risk

- Development proposals should minimise internal heat gain and the risks of overheating through design, layout, orientation and materials.

- Major development proposals should demonstrate how they

will reduce the potential for overheating and reliance on

air conditioning systems by:

- minimising internal heat generation through energy efficient design;

- reducing the amount of heat entering a building through orientation, shading, albedo, fenestration, insulation and the provision of green roofs and walls;

- managing the heat within the building through exposed internal thermal mass and high ceilings;

- providing passive ventilation;

- providing mechanical ventilation; and

- providing active cooling systems.

5.62 For some, climate change and severe weather events could cause them discomfort; for others, especially children, the elderly, and those who have certain health conditions, the effects can be potentially lethal. According to the first UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA) in 2012, there are around 2,000 heat-related deaths in the UK; it projects that this number could more than double by the 2050s. Much of this increased risk is thought to be caused by exposure to high indoor temperatures. Overheating risks to health also emerged as one of the top six key risks where more action is required in the most recent UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 2017[21].

5.63 The Climate Change Act (2008) and the NPPF (2018, paragraph 149) also require planning to take a proactive approach to mitigating and adapting to the risk of overheating from rising temperatures.

5.64 Many aspects of building design can lead to increases in overheating risk, including high proportions of glazing and an increase in the air tightness of buildings. There are a number of low-energy-intensive measures that can mitigate this risk; these include but not limit to solar shading, building orientation, solar-controlled glazing, living walls and green roof. For major developments, a landscape scheme integrating multi-functional green and blue infrastructure should be developed along the built form as this can be part of a sustainable and energy efficient development.

5.65 Developers should refer to most up to date guidance and best practice examples. The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) produces a series of guidance on assessing and mitigating overheating risk in new developments, in particular:

- TM 59: Design Methodology for the Assessment of Overheating Risk in Homes - is relevant for domestic developments; and

- TM52: The Limits of Thermal Comfort: Avoiding Overheating in European Buildings - is relevant for non-domestic developments.

These can also be applied to refurbishment projects.

Sustainable Drainage

(6) POLICY BE08: Sustainable Drainage

- All developments should incorporate appropriate Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) for the disposal of surface water, in order to avoid any increase in flood risk or adverse impact on water quality.

- Applications must meet the following requirements:

- Quantity

- on brownfield developments, SuDS features will be required to reduce discharge to previous greenfield rates or achieve a 50% minimum reduction of brownfield run-off rates;

- sites over 0.1 hectares in Flood Zone 1 will be required to submit a surface water drainage strategy. Larger sites over 1 hectare in Zone 1 or all schemes in Flood Zone 2 and 3 must be accompanied by a Flood Risk Assessment (FRA);

- Quality

- the design must follow an index-based approach when managing water quality. Implementation in line with the updated CIRIA SuDS Manual[22] is required. Source control techniques such as green roofs, permeable paving and swales should be used so that rainfall runoff in events up to 5mm does not leave the site;

- Amenity and Biodiversity

- SuDS should be sensitively designed and located to promote improved biodiversity, water use efficiency, river water quality, enhanced landscape and good quality spaces that benefit public amenities in the area;

- redeveloped brownfield sites should disconnect any surface water drainage from the foul network;

- the preferred hierarchy of managing surface water drainage from any development is through infiltration measures, secondly attenuation and discharge to watercourses, and if these cannot be met, through discharge to surface water only sewers;

- when discharging surface water to a public sewer, developers will be required to provide evidence that capacity exists in the public sewerage network to serve their development.

- Quantity

(1) 5.66 Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) are the primary means by which increased surface run-off can be mitigated. They can manage run-off flow rates to reduce the impact of urbanisation on flooding, protect or enhance water quality and provide a multi-functional use of land to deliver biodiversity, landscape and public amenity aspirations. They do this by dealing with run-off and pollution as close as possible to its source and protect water resources from point pollution. SuDs allow new development in areas where existing drainage systems are close to full capacity, thereby enabling development within existing urban areas. Reference must be made to the criteria outlined in the Essex County Council SuDS Guide.

5.67 Wherever possible, Sustainable Drainage Systems techniques must be utilised to dispose of surface rainwater so that it is retained either on site or within the immediate area, reducing the existing rate of run-off. Such systems may include green roofs, rainwater attenuation measures, surface water storage areas, flow limiting devices and infiltration areas or soakaways. This approach is commonly known as the 'surface water management train' or 'source-to-stream'.

(1) 5.68 The Environment Agency introduced a new classification system in 2011 enabled by The European Water Framework Directive. This system allows for more rigorous and accurate assessment of water quality. Some water bodies will never achieve good ecological status, however, because they have been physically altered for a specific use, such as navigation, recreation, water storage, or flood protection.

5.69 Essex County Council is the Lead Local Flood Authority. Applicants will need to prove compliance with the above drainage hierarchy and ensure sustainable drainage has been adequately utilised, taking into account potential land contamination issues and protection of existing water quality, in line with local and national policy and guidance.

5.70 The applicability of SuDS techniques for use on potential development sites will depend upon proposed and existing land-uses influencing the volume of water required to be attenuated, catchment characteristics and the underlying site geology.

5.71 When run-off does occur, treatment within SuDS components is essential for frequent rainfall events, for example up to 1:1 year return period event, where urban contaminants are being washed off urban surfaces, for all sites.

5.72 For rainfall events greater than the 1:1 event, it is likely that the dilution will be significant and will reduce the environmental risk. It is important that the SuDS design aims to minimise the risk of re-mobilisation and washout of any pollutants already captured by the system.

5.73 Developers are encouraged to refer to the Strategic Flood Risk Assessment 2018 (which maps infiltration areas) and guidance provided by the Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) for design criteria, technical feasibility, to ensure the future sustainability of the borough's drainage system. Essex County Council has produced a SuDS Design Guide (2015) to help steer what is expected from development to complement national requirements and prioritise local needs.

Communications Infrastructure

5.74 The Council recognises the growing importance of modern, effective telecommunications systems to serve local business and communities and their crucial role in the national and local economy.

5.75 High quality communications infrastructure including ultrafast broadband and mobile communication will be provided by working collaboratively with Essex County Council, communications operators and providers, and supporting initiatives, technologies and developments which increase and improve coverage and quality throughout the borough.

(1) POLICY BE09: Communications Infrastructure

- The Council will support investment in high quality communications infrastructure and superfast broadband, including community-based networks, particularly where alternative technologies need to be used in rural areas of the borough.

- Applications from service providers for new or the

expansion of existing communications infrastructure

(including telecommunications masts, equipment and

associated development, and superfast broadband) are

supported subject to the following criteria:

- evidence is provided to demonstrate, to the Council's satisfaction, that the possibility of mast or site sharing has been fully explored and no suitable alternative sites are available in the locality including the erection of antennae on existing buildings or other suitable structures;

- evidence is provided to confirm that the proposals would cause no harm to highway safety;

- the proposal has sympathetic design and camouflage, having regard to other policies in the Local Plan;

- the proposal has been designed to minimise disruption should the need for maintenance, adaption or future upgrades arise;

- the proposal will not cause significant and irremediable interference with other electrical equipment, air traffic services or instrumentation operated in the national interest; and

- the proposal conforms to the latest International Commission on Non-Ionising Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) guidelines, taking account of the cumulative impact of all operator equipment located on the mast/site where appropriate (i.e. prevent location to sensitive community uses, including schools).

5.76 The government has committed to improving broadband access. As part of this commitment the Superfast Essex Programme aims to extend the fibre broadband network as far as possible in Essex. The Council will work with broadband infrastructure providers and Essex County Council to ensure as wider coverage as possible. Upgrades to existing and new communications infrastructure, including ultrafast broadband and mobile communication will be strongly supported, including masts, buildings and other related structures, to harness the opportunities arising from new high-quality communications.

5.77 The objective of this policy is to ensure the right balance is struck between providing essential telecommunications infrastructure, conserving and preserving the environment and local amenity, particularly in the borough's sensitive areas. By its nature, telecommunications development has the potential to have a significant impact on the environment and raises issues of visual and residential amenity. Mast and site sharing, using existing buildings and structures and a design led approach, disguising equipment where necessary, can help address these concerns. Therefore, planning applications must be accompanied by detailed supplementary information which provides the technical justification for the proposed development including the area of search, details of any consultation undertaken, the proposed structure and measures to minimise its visual impact.

5.78 Although the impact from telecommunications equipment on health is a source of public concern, the government has indicated that the planning system is not the place to determine health safeguards. However, the Council will nevertheless require all applicants to demonstrate their proposed installation complies with the latest national and international guidelines. This currently requires applicants to demonstrate they comply with the International Commission of Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP)[23] which should take into account the cumulative impacts of all operators' equipment located on the mast/site.

(5) POLICY BE10: Connecting New Developments To Digital Infrastructure

- To support Brentwood's economic growth and productivity

now and in the future, all development proposals should:

- provision of up to date communications infrastructure should be designed and installed as an integral part of development proposals. As a minimum, all new developments must be served by the fastest available broadband connection, installed on an open access basis. This includes installation of appropriate cabling within dwelling or business units as well as a fully enabled connection of the developed areas to the full main telecommunications network;

- ensure that sufficient ducting space for future digital connectivity infrastructure (such as small cell antenna and ducts for cables, that support fixed and mobile connectivity and therefore underpins smart technologies) is provided where appropriate;

- support the effective use of the public realm, such as street furniture and bins, to accommodate well-designed and located mobile digital infrastructure;

- When installing new and improving existing digital

communication infrastructure in new development, proposals

should:

- identify and plan for the telecommunications network demand and infrastructure needs from first occupation;

- include provision for connection to broadband and mobile phone coverage across the site on major developments;

- the location and route of new utility services in the vicinity of the highway network or proposed new highway network should engage with the Highway Authority and take into account the Highway Authority's land requirements so as to not impede or add to the cost of the highway mitigation schemes;

- ensure the scale, form and massing of the new development does not cause unavoidable interference with existing communications infrastructure in the vicinity. If so, opportunities to mitigate such impact through appropriate design modifications should be progressed including measures for resiting, re-provision or enhancement of any relevant communications infrastructure within the new development;

- demonstrate that the siting and design of the installation would not have a detrimental impact upon the visual and residential amenity of neighbouring occupiers, the host building (where relevant), and the appearance and character of the area;

- seek opportunities to share existing masts or sites with other providers; and

- all digital communication infrastructure should be capable of responding to changes in technology requirements over the period of the development.

- Where applicants can demonstrate, through consultation

with broadband infrastructure providers, that superfast

broadband connection is not practical, or economically

viable:

- the developer will ensure that broadband service is made available via an alternative technology provider, such as fixed wireless or radio broadband; and

- ducting to all premises that can be accessed by broadband providers in the future, to enable greater access in the future. Or:

- The Council will seek developer contribution towards off-site works to enable those properties access to superfast broadband, either via fibre optic cable or wireless technology in the future.

5.79 Fast, reliable digital connectivity is essential in today's economy and especially for digital technology and creative sector. The provision for digital infrastructure is important for the functioning of development and should be treated with importance.

5.80 Digital connectivity supports smart technologies in terms of the collection, analysis and sharing of data on the performance of the built and natural environment, including for example, water and energy consumption, air quality, noise and congestion. Where it is appropriate and viable to do so, development should be fitted with smart infrastructure, such as sensors, to enable better collection and monitoring of such data. As digital connectivity and the capability of these sensors improves, and their cost falls, more and better data will become available to improve monitoring of planning agreements and impact assessments.

5.81 Digital connectivity also supports smart technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), wireless motion sensors and Virtual Reality (VR) which are increasingly used to assist an ageing population and people living with dementia, by reducing isolation, promoting independent living and assisting and complementing care and support.

5.82 Provision of high capacity broadband will support businesses and attract investment to Brentwood. It allows residents and businesses to access essential online services, social and commercial networks. It also has the potential to increase opportunities for home-working and remote-working, reducing the demand on travel networks at peak periods. The importance is demonstrated by recent census returns which show that the biggest change in journey to work patterns in the last 20 years has been the increase in people working from home.

5.83 The Council aspires to have ultrafast broadband or fastest available broadband at all new employment areas and all new residential developments through fibre to the premises/home (FTTP/H). Fibre to the curb, copper connections to premises and additional ducting for future provision will be considered if developers can show that FTTP/H is not viable or feasible.

5.84 It is recognised that at present, in some rural areas of the borough, fast, reliable broadband is not available as it is uneconomic or unviable to serve small numbers of properties in isolated locations. These places generally have poor access to other facilities and as such would not be expected to provide significant levels of growth. Lack of fast, reliable broadband or lack of scale to deliver broadband may be considered as unsustainable in these locations.

5.85 Where new development is proposed in rural areas, investment in superfast reliable broadband will be required, subject to viability. This means that developers should explore all the options, and evidence of this engagement should be submitted with a planning statement.

(13) Transport and Connectivity

Sustainable Transport

5.86 Sustainable transport is a key component of sustainable development, for its many benefits go beyond helping the environment. It encourages an active lifestyle, contributes to improving air and noise quality, helps improve public health, provides safer environments for children, increases social interaction in the neighbourhoods and can save travel time by reducing congestion.

5.87 Sustainable transport refers to:

- Transport strategies that increases accessibility/mobility while minimising traffic volume and overall parking levels, for example allocating development in highly accessible locations, or providing public transport and a cycling network (Policy BE11 Strategic Transport Infrastructure, Policy BE12 Car-limited development, Policy BE13 Sustainable Means of Travel and Walkable Street, Policy BE14 Sustainable Passenger Transport, Policy BE17 Parking Standards)

- Means of transport which reduces the impact on the environment such as sustainable public transport, low emission vehicles, vehicle charging points and car sharing, as well as non-motorised transport, such as walking and cycling (Policy BE14 Sustainable Passenger Transport, Policy BE15 Electric and Low Emission Vehicle,).

- Mitigating the transport impact of development (Policy BE16 Mitigating the Transport Impacts of Development)

(2) 5.88 Many aspects of transport and travel need to be considered, including reducing the need to travel, encouraging walking and cycling to reduce dependency on car travel and to improve public health, making public transport cleaner and more accessible to all users.

5.89 It is also important that we consider car ownership and be realistic about the fact that most households in the borough will own a car. While public transport links into London are good for Brentwood town and other areas along the transport corridors, villages are more remote with less good access. Therefore, it is acknowledged that some level of car travel and parking considerations will remain important for Brentwood as we consider the future.

(13) POLICY BE11: Strategic Transport Infrastructure

- Maximising the value of railway connectivity and

Elizabeth Line

- The Council supports the fast high-capacity transport links into London from Shenfield and the improved linkages from Elizabeth Line, maximising the potential for an overall improvement to borough rail services, and mitigating environmental and transport impacts as a consequence of the scheme. This would be achieved through improvements to pedestrian and cycle infrastructure and bus services linking both new and existing developments to the train stations, and introduction of parking controls where needed.

- Development in proximity to the railway stations will demonstrate how the schemes connect to the surrounding walking, cycling and public transport links to the station. The proposed schemes must offer direct routes, as well as easy, effective orientation and navigation to the stations.

- Improving multimodal integration and/or capacity at

train stations

- The Council will work with the highway authority,

statutory bodies and key stakeholders, including public

transport operators, to secure funding for:

- improving the public realm and circulation arrangement as well as achieving multimodal integration around both Brentwood and Shenfield stations given the potential increased usage and footfall expected to arise from Elizabeth Line;

- improving the public realm, circulation arrangement and capacity of West Horndon station as well as creating associated multimodal interchange through phases to support new residents and employees;

- improving the public realm and circulation arrangement as well as achieving multimodal integration around Ingatestone; and

- bus services connecting the developments sites to stations;

- The Council will consider the scope for Park and Ride/ Cycle/ Stride schemes where the demand and impacts are assessed within a detailed feasibility study.

- The Council will work with the highway authority,

statutory bodies and key stakeholders, including public

transport operators, to secure funding for:

- Delivering improvements to the highway infrastructure

capacity

- The Council will continue to work with the highway authority, statutory bodies and key stakeholders to coordinate and, where appropriate, deliver improvements to the highway network and other suitable non-highway[24]measures.

- Any significant impacts from the development on the transport network on highway safety must be effectively mitigated to an acceptable degree in line with Policy BE16 Mitigating the Transport Impacts of Development.

- Development close to schools and early years & childcare facilities should facilitate an attractive public realm that is safe for children and encourages walking and cycling to address the impacts of school run traffic, in line with ECC's Developers' Guide to Infrastructure Contributions.

5.90 This policy seeks to align strategic transport infrastructure improvements with Brentwood's proposed allocations and economic growth and to contribute to health and well-being whilst preserving the environment. This would be achieved by maximising the value of Elizabeth Line, improving the capacity of the stations and road network, ensuring the main settlements and new development have convenient access to high quality and frequent public transport services which connect to the town centre, main employment centres, rail stations, ports and airports in the wider region.

5.91 Development proposed within this Plan will only be deliverable and supported if suitable transport measures and investment are led, coordinated and, where appropriate, delivered by Brentwood Borough Council and strategic partners. Development should seek to enhance transport, particularly public transport, and wider connectivity between new and existing employment areas.

Maximising the value of railway connectivity and Elizabeth Line

(1) 5.92 Previously known as Crossrail, the new Elizabeth Line is a 118 km railway under development crossing through the heart of London, enabling access between Reading and Heathrow in the west, through central London to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east. The full route is expected to be fully operational by December 2019. The arrival of Elizabeth Line will provide an improved and more frequent service to Brentwood's residents and visitors thus benefiting businesses and facilitating growth. The Council will work with partners to improve the station environment at both Brentwood and Shenfield stations, specifically in terms of non-motorised users and enhanced public transport access, with new forecourt and pedestrian crossing facilities.

5.93 It is expected that the introduction of this new railway will have both positive impacts, as a result of additional rail trips, and potentially negative impacts, with potential for increased travel by car to access the stations (Transport Assessment, PBA, 2018). There will be a need to monitor and review the situation once the services are operational. Any impacts identified should be addressed through the implementation and promotion of sustainable transport measures, for example the provision for non-car modes and the implementation of parking restrictions and pedestrian wayfinding system.

5.94 The proximity of new housing developments close to railway stations can provide the opportunity to improve cycling and walking infrastructure for shorter distance trips, to access rail services. Improving links to Brentwood and Shenfield stations will benefit both existing population as well as the new Local Plan developments within easy access of the stations. Proposed allocations and future development near Brentwood and Shenfield stations are required to demonstrate that the planning and design for movement connect well to the surrounding walking, cycling and public transport links to the station, and give priority to pedestrians and cyclists.

(3) Improvements to the train stations

5.95 In order to support a transit-oriented growth strategy and support projected travel demands from future development as well as provide the opportunity for non-motorist travel, it is important to achieve integration of transport modes. This should support regional trips by public transport and reduce pressure on the road network at the critical peak period. The Council will encourage improvements to the public realm surrounding existing train stations and look to improve access, interchange facilities, installation of wayfinding signs and introduce parking control where appropriate. Park and Ride/Cycle/Stride schemes to improve access to the stations will be considered subject to a future detailed feasibility study prepared by the Council.

(4) 5.96 The railway stations in the borough have potentials to assist in providing additional benefits to sustainable travel. New development should seek to provide new or improved links and access to the station. Where appropriate contributions will therefore be sought from nearby developments:

- Brentwood station: located on the Great Eastern Mainline, Brentwood station is served by TfL rail services operating between Shenfield and London Liverpool Street and Abellio Greater Anglia services operating between Southend Victoria and London. The emphasis on accessibility to both Shenfield and Brentwood stations will be on sustainable travel as a means of access, with improvements to pedestrian and cycle infrastructure and bus services, linking both new and existing developments near the stations, and on introducing new parking controls where needed to discourage parking around the stations, therefore reducing car travel.

- Shenfield station: also located on the Great Eastern Mainline, Shenfield station is served by TfL and Greater Anglia rail services to Stratford and London Liverpool Street station and Greater Anglia services to Southend Victoria, Colchester Town, Ipswich, Braintree and Clacton-on-Sea, as well as some services to Norwich. From late 2019 it will be the terminus of the Elizabeth Line which will run from Reading and Heathrow Airport in the west through London. During 2014 JMP Associates undertook a station parking study for Shenfield prior to the development of the Elizabeth line. From the Rail User Survey carried out as part of the study, the study demonstrates that with the introduction of better bus services to the station, a reduction in the number of people who park at Shenfield who live in the vicinity as well as from any future Local Plan developments in the region could be witnessed, reducing overall traffic on the local network. As mentioned above, enhancement to Shenfield station would centre around improving pedestrian and cycle infrastructure and bus services and where necessary, parking controls.

- West Horndon station: West Horndon station is on the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway line and is served by C2C with two trains per hour to London Fenchurch Street and Shoeburyness. It is currently identified that parking capacity is fully utilised most weekdays for commuters into London from the A127/A13 corridors. The location of a number of the Local Plan development sites will mean that West Horndon Station will play an important role in future transport provision. The Transport Assessment (PBA, 2018) proposed that over the lifetime of this Plan, the improvements to the station, bus and cycle infrastructure and interchange facilities are phased to create a new integrated transport hub. An increased capacity on the existing train service will be central to the new cycling, walking and bus movements of the new residents and employees. To ensure the new development will provide convenient access to the future interchange at West Horndon, the Transport Assessment (PBA, 2018) proposed that interim bus service(s) connecting the developments sites to the interchange should be built into the development agreements to be funded. This should allow time for enough customer demand for a commercial operator to take on the routes. This is particularly the case with Dunton Hills where new opportunities will exist.

- Ingatestone station: Ingatestone railway station is on the Great Eastern Main Line, currently served by Greater Anglia. New development should seek to provide new or improve links and access to Ingatestone station.

Delivering improvements to the highway infrastructure capacity

5.97 As the backbone of our transport system, roads keep the population connected and the economy flowing. In light of planned development, it is important to grasp the opportunity to transform our roads and the experience of driving on them, whilst also addressing strategic imperatives such as economic growth and climate change.

5.98 It should be noted, however, that providing additional highway capacity will only have a short-term impact and may be quickly taken up by suppressed traffic. Therefore, investment in providing alternatives is important. Non-highway measures[25] such as sustainable transport measures and behavioural change that go beyond physical improvements could assist in alleviating pressures on the highway network. These measures are embedded in other policies in this Plan.

5.99 The Council is working with Associations of South Essex Local Authorities (ASELA) to prepare a statutory Joint Strategic Plan (JSP) which will identify ways to transform transport connectivity, among other required work to deliver growth. This work will inform public transport services needed to follow suit if the wider development needs of south east England are to be sustainably provided.

5.100 In Brentwood, the strategic highway infrastructure includes:

- the A12 which connects the market town and major settlements in central Brentwood Borough to London and the wider region, providing access to services, jobs and recreation;

- the A127 which travels through the south of Brentwood Borough and connects it to London, Basildon, Rochford, Southend, Southend Airport and surrounding employment areas. The A127 corridor is a vitally important primary route for the south of Essex;

- the M25 in the west which connects Brentwood Borough to London and Stansted Airport;

- and associated key junctions.

5.101 The Transport Assessment (PBA, 2018) assessed how the highway network within the borough copes at a strategic level as a result of the new Local Plan Development and committed developments within adjacent local authorities that would likely have an impact on Brentwood Borough highways. This work identified a number of junctions that may require mitigation as well as a number of non-highway[26]related mitigation measures. The results of the modelling and junction assessments highlight the need to continue to monitor throughout the Local Plan period to identify any additional impact from other schemes on the highway network in Brentwood, such as the Lower Thames Crossing project, the A127 and any highway effect from the opening of the Elizabeth Line. Since the level of growth planned along the A127 and A12 are reliant on new and improved strategic infrastructure of regional and national importance (including the Lower Thames Crossing), the Council will continue to work with the highway authority (Essex County Council), statutory bodies (including Highways England), the Essex Heart and Haven Strategic Transport Boards[27] other partners (including the ASELA and the A127 Task Force), and developers to secure the mitigation measures to the highways and related junctions to deliver growth. The impact of individual access junctions for individual sites would be expected to be undertaken by promoters of individual sites.

(2) 5.102 It is recognised that existing mitigation undertaken by third parties is being considered and will assist in improving capacity of the highway network in the borough. These include:

- A127/A128: several studies, led by Essex County Council, have been progressing on the A127 corridor between Southend-on-Sea in the East to the M25 in the west, the final section of this road is within Brentwood Borough. Within the A127 Corridor for Growth study[28] there are individual pieces of work currently at various stages of planning and development, many of which are focussed on interchange capacity and/or safety improvements. Continued joint working with ECC and other neighbouring authorities will be important, so any outcomes from this study can feed through to the South Brentwood Growth Corridor Masterplan;

- M25 Junction 28: Highways England are currently undertaking work to develop improvements at M25 Junction 28[29]. Further engagement will be required with Highways England on this scheme;